Photographic Art in the 1970s

In the early 1970s, very few people considered

photography to be a legitimate artform.

Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico (1941), Ansel Adams

“Photography is not, to begin with, an art form at all”

So wrote Susan Sontag in On Photography, a celebrated collection of critical essays published in the New York Review of Books between 1973 and 1977. She continued, “Photography is not an art like, say, painting and poetry.” Eventually, she would publish a partial refutation of these opinions in her 1993 book Regarding the Pain of Others.

But her initial opinion was the general perception of the world when I began working in photography in my early 20s. At that time there were a precious few who were considered to be “fine-art “ photographers. Almost none earned a living selling their prints as art, and the exception proved the rule. The rest were left executing commercial commissions, working in academia, or finding other ancillary routes to support themselves at the fringes of the medium.

Even now-celebrated artists like Ansel Adams and Georgia O’Keefe took corporate assignments in their early years. O’Keefe traveled to Hawai’i in 1939 to create print ads for the Hawaiian Pineapple Company (now Dole Pineapple), as Adams did, first in 1948 on assignment for the National Park Service, and again in 1957 for Bishop National Bank of Hawai’i (now First Hawaiian Bank).

Adams and O’Keefe, respectively, on assignment in Hawai’i for corporate clients

The 1970s were a time of substantial change in the public view of the medium, and architects and interior designers began using photographic imagery as a contemporary aspect of architectural design. At the same time in 1975, I began work in the San Francisco office of the world’s largest stock photography agency, The Image Bank.

My job as a researcher gave me direct access to images made by many of the outstanding photographers of the day, as well as ongoing contact with advertising agencies, publishers, and some of these same architects and interior designers working in the vanguard of incorporating photographic imagery into their design work. Unknown to my employer at the time, I began including my own work under a pseudonym and found my images gained a positive response and were occasionally selected for final installation.

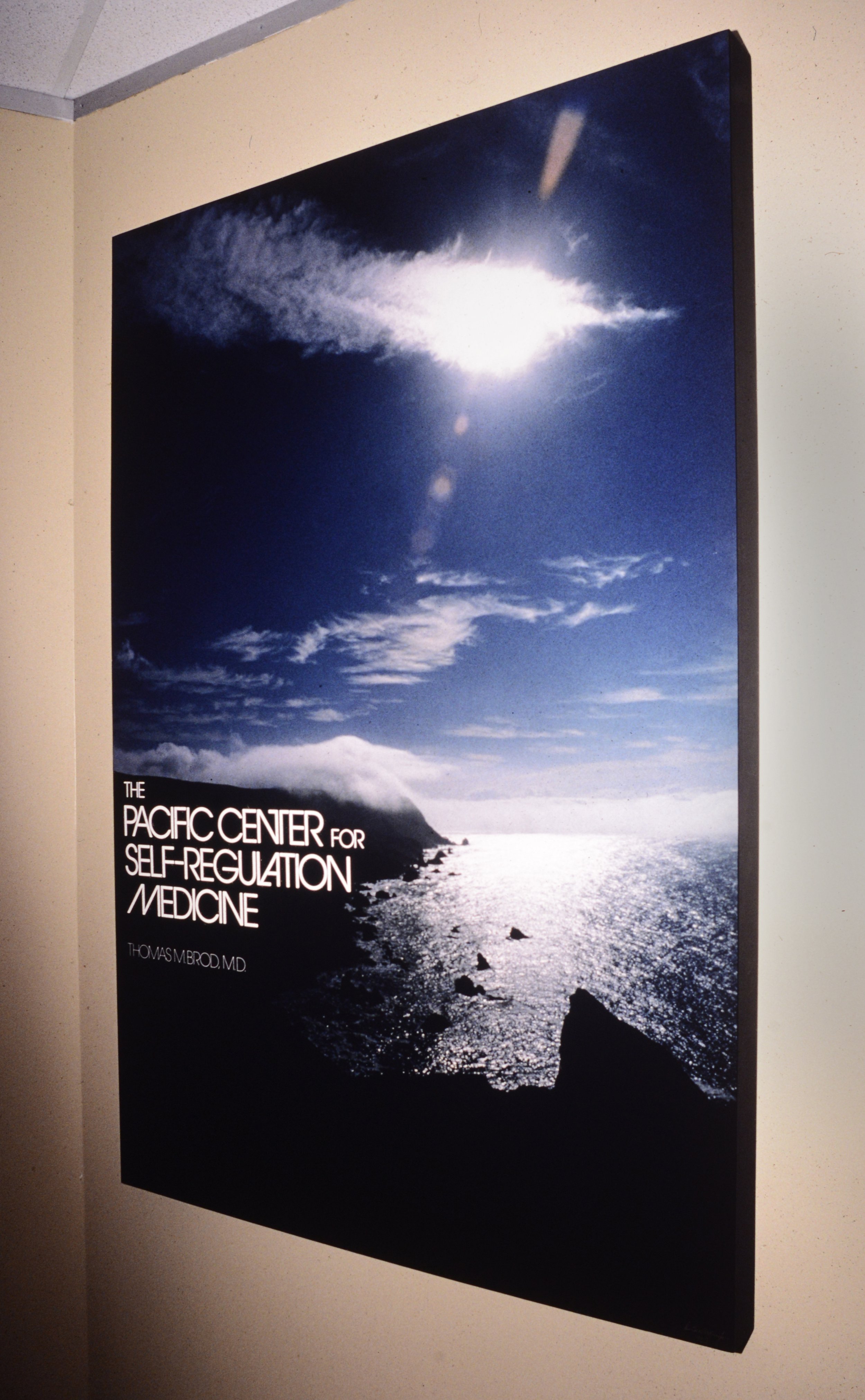

Pacific Center for Self-Regulation Medicine, Mill Valley, California, 1978

This chromogenic development print was made from one of the author’s images of the headlands of Marin County, north of San Francisco.

Over the following years, this design motif began to appear everywhere from the offices of The Muppets in New York to the Bank of America in San Francisco. Manufacturers recognized the opportunity and embraced it. Eastman Kodak Company, who we referred to as “The Great Yellow Father” and 3M, the vendor of the Scanamural process, both invested millions in promoting this new design concept.

Muppets Offices, New York, 1980

These murals on deep pile carpet were made using the 3M Scanamural process, using still photographs from The Muppet Movie in 1979.

I also contributed, first as Litchfield Associates (my middle name) managing projects at The San Francisco Bay Club, Caterpillar Tractors, the world headquarters of Bechtel, and American President Lines, eventually partnering with a Newport Beach competitor in 1979.

San Francisco Bay Bridge (1935), Bechtel World Headquarters, San Francisco. Stretched fabric Scanamural designed, fabricated, and installed by Litchfield Associates, 1978

It was an exciting time, and I ultimately left the business to focus full-time on my photography, joining the late Fred Lyon’s South-of-Market studio in San Francisco before beginning work on my book The Unseen Peninsula in 1983.

In 1999, commensurate with the publication of my second black-and-white landscape monograph, Eighteen Days in June, I left the San Francisco scene for good, building a studio and darkroom at my new home in Montara on the California coast, amd beginning the development of my cameraless artwork.